2021 Campbell Creek Science Center Poster

Front side

Back side

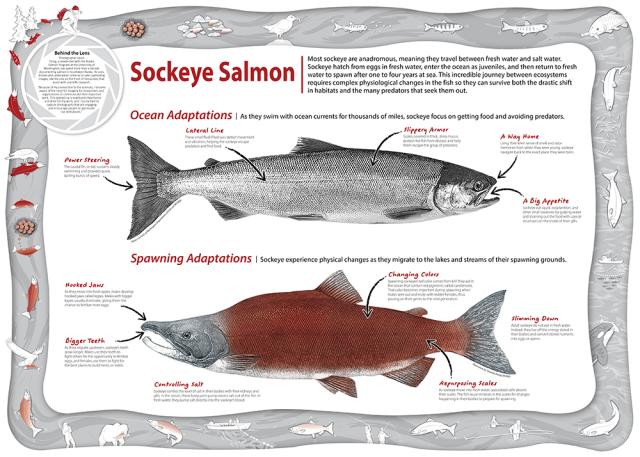

Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka)

Sockeye salmon churn through the clear waters of an Alaska lake on the way to their spawning grounds. As they transition from the ocean into fresh water, their sleek, silver bodies turn brilliant red and green. A bright red male, bearing jagged teeth and a new fleshy hump, signals his fitness and maturity to the females around him.

Sockeye, also called red salmon, are one of the five species of Pacific salmon found in Alaska. Over millions of years, sockeye have evolved complex adaptations that enable them to move from fresh water to the ocean and back again. Throughout their life cycle, sockeye connect and sustain ocean and forest ecosystems and the wildlife and people that live in those places.

Photo Credit (front): Jason Ching

To learn more about sockeye salmon, visit Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s species profile.

The poster is available at the BLM Alaska Public Information Center at 222 W. 7th Ave. Please call ahead at 907-271-5960.

Behind the Lens: Full Interview with Jason Ching

Jason Ching is an environmental researcher with the Alaska Salmon Program at the University of Washington. He is also a talented photographer. To learn more about Jason and the role of photography in his scientific work, check out this interview (below).

How long have you been taking photographs?

I have been carrying around a camera with me for most of my adult life, but I did not really start pursuing photography seriously until about my third season of working in Alaska (summer 2010). So, about 10 years. The amazing scenery and wildlife found in Alaska are what motivated me to really invest myself into photography and want to share and spread an appreciation for our natural areas.

What is your science background?

I went to the University of Washington and received my bachelor's degree in aquatic and fishery sciences in 2008.

Does science influence your photography, and does photography influence your scientific work?

Science, and the understanding about how these salmon ecosystems function, plays a big role in how I approach nature photography. Having a background in the natural sciences not only helps me to home in on salmon behaviors and movements but also reminds me to be aware and respectful in how I approach and interact with subjects in nature as well.

Photography started out as nothing much more than a hobby for me, merely taking pictures to show friends and family the gorgeous landscapes and wildlife in Alaska. But because of my connection to the sciences, I became aware of the need for imagery for researchers and organizations to communicate their important work. This opened up a new-found importance and drive for my work, and I try my best to capture photographs that are engaging and encourage people to appreciate our wild places.

Photography has definitely had an influence in our scientific research as well. Recently we used drones to conduct aerial surveys of salmon spawning grounds, allowing us to get high-resolution counts of spawning salmon. We also use trail cameras to observe bear behaviors on salmon streams, and there is new work underway to use time-lapse photography to attempt to develop a new system for counting salmon moving up streams to spawn. There are many ways in which photography is assisting or playing the primary role in our scientific work today and it seems like every year we are developing a new way to use imagery to help us out in the field.

When and why did you start using drones and underwater cameras to capture footage?

I picked up a drone nearly as soon as they were available to consumers in 2013. I remember being on the fence about purchasing one—and actually had not planned on one right away— until I saw footage from a research team doing some preliminary work using drones to measure whales in the field. After I saw that video, I was immediately set on getting one and I remember having one shipped the next day to myself while I was already in Alaska. One of my favorite parts of nature photography is to come up with creative ideas to get unique and engaging shots, and drones really offered that new perspective on our salmon runs that had not been widely seen at the time.

I have probably been using underwater cameras for about as long as I have been using drones, maybe a bit longer. Working with salmon and having a strong connection with being underwater, I feel like it was inevitable for me to want to explore Alaska from beneath the surface of the water. With the help of a couple of really good friends and colleagues who were already long experienced in underwater photography, I got a setup going rather quickly and was immediately hooked. It is an incredible experience to really share the same space as these fish.

Patience is certainly the biggest key and factor in getting the images I look for in nature. Wildlife photography is incredibly unpredictable. To get the photographs I envision, sometimes it means I am sitting in a single location in a really cold stream for hours or taking the time to observe salmon runs from the sky to line up the best image. I approach both underwater and drone photography with patience. A lot of times, before I break out the cameras, I take time to observe what is going on. Having a thoughtful approach is really helpful.

What is the story behind the image chosen for the poster?

The image chosen for the poster was part of a photo experiment to capture a different perspective of these salmon. In a lot of the underwater images I take, I often use a wider-angle lens and shoot from more of a side angle to the salmon. I thought it might be an interesting look to have the salmon facing directly at the camera with a bit of a longer lens in this case, and it made for an engaging photograph. I am always trying to come up with new ways to capture images of familiar subjects. Thinking outside of the box and getting creative to obtain unique photographs are definitely some of my favorite parts of photography.

What is the coolest or most interesting thing you have encountered while doing salmon research and photographing salmon?

Last summer (2019) we had an amazing opportunity to watch Lake Iliamna’s rather elusive freshwater seals hunt for migrating sockeye salmon. Throughout my 12 summers of working on Lake Iliamna we had seen seals somewhat regularly as we conducted studies at various sockeye salmon spawning locations, but they often swam away as we approached within a couple of hundred yards of them. Last summer we were able to observe up to half a dozen seals chasing around large schools of sockeye salmon in the lake, and it was an incredible sight to watch these seals methodically work to catch their meals.

What is your favorite fact about salmon?

The anadromous life cycle of salmon is definitely one of the coolest facts about salmon, in my opinion. Most of us are familiar with the salmon life cycle, but to understand that because they move across so many ecosystems, they also support an incredible variety of life, that to me is the power and magic behind salmon. As newly emerged fry to adults, from streams to oceans, salmon are really the lifeblood of so many environments across their entire life cycle, providing nutrients to everything from trees to whales.

Beyond scientific work, do you have personal connections to salmon?

Growing up in a family that was closely tied to recreational fishing in the Pacific Northwest, salmon were certainly a big part of my life from an early age. That connection to the outdoors and a continuous passion for understanding the natural world is really what drove me to go to school in the fishery sciences. Learning more about how these intricate ecosystems function, as well as how salmon play a role in commercial fisheries and in communities and cultures, has further deepened my connection with salmon and makes me eager to tell their story.