You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

More than a Throwback, Historical Aerial Imagery Provide Irreplaceable Data

In a world where it seems everything is digital, computed, and programmed, a trove of aerial images dating back decades are just beginning to prove their lasting value for federal land managers and the public.

Starting in the 1960’s and spanning into 2008, Bureau of Land Management Alaska pilots and aerial photographers documented Alaska’s vast landscape from airplanes, according to BLM Alaska Intelligence Imagery and Geospatial Analyst Chris Noyles.

“We had our own plane, our own cameras,” Noyles shared. “We flew primarily for conveyance staff and the surveyors in the field.”

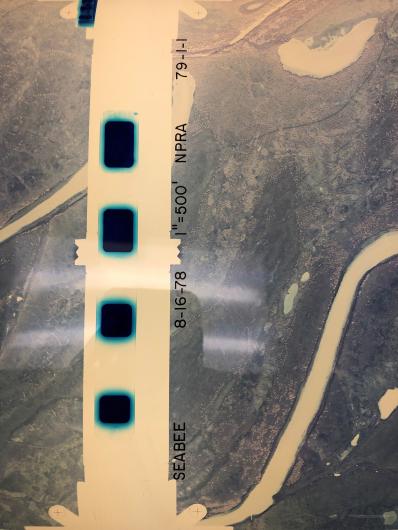

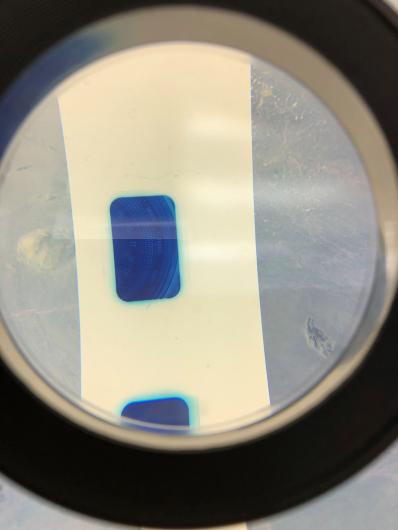

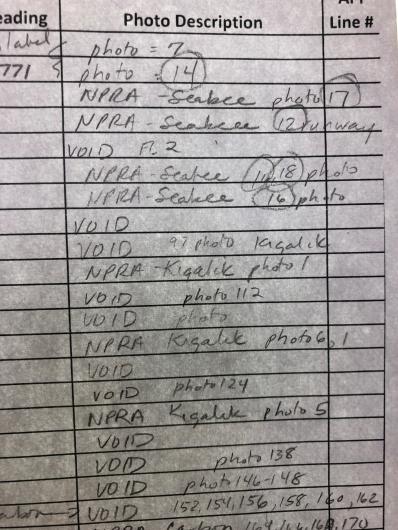

GIS Volunteer Mary Hudson-Kelley has been working to digitize the collection and explained how to make sense of what you see now as she empties a canister and unrolls the film across a light table.

“On the film, what would be there is a clock, there’s sometimes an altimeter, something that might say the date, and a little bubble to show whether or not it’s level,” Hudson-Kelley pointed out the tiny circles lining one side of the image.

BLM also inherited and stored film rolls from other agencies, including the Department of Defense and NASA, because they had the cold storage needed to preserve the film. Some of those images date back to 1938, according to Cathy Hillis, Geospatial Manager for the Bureau of Land Management’s Alaska State Office.

“The end result is over 142,000 frames of imagery.” Hillis easily accounted for the stock, “Covering almost every part of Alaska.”

As part of BLM Alaska’s Geospatial Information Systems (GIS) program the division also included a film processing lab and later included film scanners to convert the diapositive film (the opposite of a negative film) into digital images.

Noyles and Hudson-Kelley recount the history of the program in an office mostly quiet while BLM staff telework from home.

Now the project is pride of Hudson-Kelley, the dedicated BLM volunteer, who brings previous GIS experience to the project. Hillis successfully recruited Hudson-Kelley from an Anchorage hiking group.

“Mary (Hudson-Kelley) has worked two or three days a week since June 2017, racking up over 900 volunteer hours, reviewing historical aerial film and confirming and updating metadata about each frame,” Hillis details just how vital Hudson-Kelley's volunteerism has been. “She reviewed more than 84,000 frames of film. Other staff have boxed and shipped over 380 rolls of film and sent them to the USGS Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) for scanning and inclusion in the digital imagery archive.”

“The end goal is that anybody can go to the internet,” Hudson-Kelley fired up her computer, “Go to the GIS site and pull up a picture and say this was taken at such and such time and place.”

Hudson-Kelley suggested some ways the public might put the imagery to use; Academics might use them for reference, recreation enthusiasts to understand new terrain, private pilots for better visuals.

Hillis shared a variety of ways agency can use the films: fire history, cadastral survey, glacier monitoring and tracking climate change, proof of traditional use and occupancy, locating legacy wells, and wildlife observations.

The possibilities are endless, they all agreed.

While at first glance, some may think this imagery is simply out of date, in fact, they hold unique data of Alaskan landscapes in a specific time, called place-in-time data. That data can’t be recreated or modeled the same way it was captured in the moment.

Visuals of burn scars from 70 years ago tell foresters and wildlife biologists how soon plants and animals will return to an area after a wildfire. Images of a far-flung glacier provide visual clues for climate research across the state.

All of this information can be considered when BLM Alaska’s leaders make decisions regarding recreation access, land conveyances, permit or conduct prescribed burns, carry out reclamation projects, or allow for new surface developments.

The digitization project is nearing completion in Alaska and hundreds of containers with brightly colored tape that once neatly lined the walls of a special storage refrigerator have now been shipped and the refrigerator walls are empty. The fridge will be shut down and the film will live on in digital form, far exceeding their original purpose.

Melinda Bolton, Public Affairs Specialist

Related Stories

- Legacy on the land: BLM Firefighter James Will Bennett's homesteading heritage in New Mexico

- Collin Ewing discovers personal link to the BLM’s earliest roots

- Joining forces to clear the way: Fire and aviation crews from Idaho and Nevada assist in Southeast storm relief

- A Paw-powered Legacy

- Preserving the past across the Plains: BLM Montana-Dakotas Cultural Resources staff safeguard America’s storied history

Office

222 W 7th Avenue #13

Anchorage, AK 99513

United States