Abandoned Mine Lands & Environmental Cleanup

The BLM defines an Abandoned Mine as an abandoned hard rock mine on or affecting public lands administered by the BLM, at which exploration, development, mining, reclamation, maintenance, and inspection of facilities and equipment, and other operations ceased as of January 1, 1981 (the effective date of BLM’s Surface Management regulations codified at 43 CFR Subpart 3809) with no evidence demonstrating that the miner intends to resume mining. This includes, but is not limited to: acid and caustic rock drainages, waste rock, mill tailings, and retort waste. Physical safety hazards may include steep slopes, adits, winzes, raises, buildings, high walls, settling ponds, other water retaining features, as well as other related dangerous structures. For many abandoned mines, no current claimant of record or viable potentially responsible party exists. Abandoned mines generally include a range of mining impacts or features that may pose a threat to water quality, public safety, and/or the environment.

History

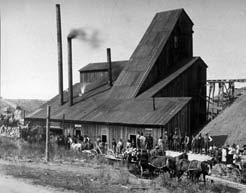

Mining in our nation’s western lands and waters for precious metals was a powerful force behind the exploration and settlement of the American West. Hard rock mining is non-coal mining environments where environmental impacts such as acid-mine drainage, heavy metal contamination, and threats to water quality and the environment are of concern. Hard rock minerals in this context generally include, but are not limited to, gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, magnesium, nickel, molybdenum, tungsten, uranium, and selected other minerals.

Most hard rock minerals are locatable minerals under the 1872 Mining Law. The lure of fortune-making and legislative incentives fostered by the 1872 Mining Law provided the economic base on which many remote communities were established and on which our country prospered. Often driven by economic expansions or wartime needs, these communities and the mines that supported them went through many “booms” and “busts.”

The large-scale gold rushes in Alaska, California, Colorado, Idaho, and Nevada ushered in a redistribution of our nation’s population. But, even at the height of the gold rush, much of the West was not settled. Today, 11 of the 20 states with the fastest population growth are in the West, where BLM-administered public lands abound. As a result, the number of visitors to BLM public lands has doubled in the past 2 decades—to nearly 60 million visitors in 2011. The West has become America’s Backyard.

Until the latter half of the 20th century, few environmental regulations existed to encourage mining companies to minimize or prevent the environmental impacts caused by their facilities. Historic mines produced precious or profitable metals such as gold, silver, copper, lead, and platinum. However, the aftermath of such mining left behind unrecovered or subordinate minerals and other processing byproducts such as arsenic, mercury, cyanide, lead, and acids. Such wastes made their way into the soil and water. Many of these mines involved extensive underground workings. Mines also needed processing facilities such as mills to crush the ore and smelters to produce the metals. Gold discoveries in streams led to destructive “placer” mining in Alaska and California.

Hydraulic mining in California and dredge mining in Montana resulted in stream siltation and extensive erosion, scarring landscapes in the process. Hydraulic mining required millions of gallons of water. Entrepreneurs dammed streams and built complex systems of ditches and wooden flumes to direct water to the mining operations. By 1859, 5,726 miles of aqueducts ran through the California mining region.

As easily accessible ore deposits were exhausted, individuals and companies developed new technologies to locate, extract, and process minerals and ores from more challenging locations. Mining and mineral processing equipment became more complex, and profitable mines began to require larger footprints. Technologies such as heap leach and vat processing significantly enhanced recoveries from lower-grade ores. Unfortunately, the necessary chemicals for these new technologies, such as mercury and cyanide, at times escaped into the environment due to inadequate controls and practices. When economic “busts” eventually arrived due to metal price drops, hardrock mining operations ended and the companies folded or moved elsewhere. The mines were shut down or abandoned and usually never restored and/or remediated. Environmental and/or physical risks remained leaving behind conditions that are hazardous to people and our public lands and resources. As a result, it has left thousands of potentially dangerous abandoned mine features were left behind on the public lands. This is the Old Legacy of mining on public lands that the BLM works to address.

The old legacy of these abandoned mines, safety hazards, and contaminated land and water forecast the need for environmental cleanup and safety measures. The transition from the Old Mining Legacy to the new AML program legacy was sparked by the passage of environmental legislation in the mid- to late-20th century. Laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), Clean Water Act, Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA), and Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) were enacted to address environmental and public health concerns. These laws help prevent environmental contamination and safety issues from developing in the future. The BLM’s programs and funding have responded to the needs of AMLs on public lands and work in support of these laws.

Timeline

1890s: Dredge mining technologies introduced.

1900s: By 1900, U.S. population grows with the geographic distribution shifting West.

1941: United States enters World War II. Gold mines ordered to close to focus mining on strategic metals and minerals, such as lead, zinc, copper, and tungsten which were needed for the war effort.

1945: Cold War begins. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission calls upon prospectors to begin a full-scale uranium industry.

1946: BLM created through a merger of the General Land Office (GLO) and the U.S. Grazing Service.

1951: Korean War increases demand for strategic metals and minerals, such as lead, zinc, copper, tungsten, and uranium.

1960s: Economic & technology boom ushers in an increased need for base and industrial metals and minerals, such as copper, lead, zinc, iron, nickel, molybdenum, niobium, tungsten, cobalt, sand, clay, gypsum, and barite.

1969: Environmental movement begins and the federal government enacts federal law focused on environmental protection.

- NEPA (1969)

- FLPMA (1976)

- CWA (1977)

- SMCRA (1977)

- CERCLA (1980)

1970s: Use of cyanide heap leach mining to extract gold and other metals begins.

1980s: Agencies develop regulations and programs to implement new environmental laws. BLM issues Surface Management Program regulations (1981). BLM Hazardous Materials Program established (1985).

1989-1996: BLM AML Task Force formed. BLM conducts initial AML inventory activity.

1997: AML Task Force reports that in an area of 7.4 million acres, approximately 7,000 AML sites were verified containing over 6,600 safety hazards. BLM establishes AML program. BLM AML pilot watershed projects launched in the Upper Animas River (Colorado) and Boulder River (Montana).

1998: AML inventory grows to 8,000 sites. Clean Water Action Plan released; provides blueprint for restoring and protecting the nation’s precious water resources. Third AML pilot watershed project launched in Cottonwood Wash, Utah. Mine Safety Health Administration (MSHA) launches first national outreach campaign, the “Stay Out-Stay Alive” initiative, to educate the public about AML hazards.

1999: First 10 AML watershed sites restored. Restoration projects underway on 120 AML sites in 31 watersheds in 12 states. 50,000 AML safety brochures distributed to educate public land visitors and users about AML hazards.

Abandoned Mine Lands Program: A New Legacy

A New Legacy is unfolding as the BLM works to restore public lands impacted by two centuries of historic hardrock mining. Consistent with its mission to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations, the BLM is fostering a New Legacy to bring unsafe and contaminated abandoned mines to a restored, safe, and sustained state. Building an enduring New Legacy requires commitment of resources, actions, and expertise. The BLM implements a phased approach, singularly focused on restoring and reclaiming lands and waters.

The BLM implements our approach in partnership with other federal agencies, state agencies, local governments, and private and not-for-profit organizations. These partnerships provide the best way to collaborate on actions, leverage vital resources, and ensure success. Since the inception of the AML program, the BLM and its partners have been committed to addressing high-risk and high-priority abandoned mine sites to protect public health and safety.

This approach consists of:

Discover:

Locate and assess hazards at abandoned mines. During this phase, potential risks are evaluated and the measures for addressing hazards are determined. The abandoned mines that pose the greatest threat to the public and the environment are prioritized for funding. All of this is done within the context of the BLM’s available funding and the agency’s many programs and priorities.

Restore:

Address the hazards at abandoned mines with the goal of protecting the public and environment. During this phase, the BLM and its partners implement intermediate and permanent measures to restore abandoned mines and determine long-term monitoring and maintenance requirements.

Sustain:

Protect the public and the environment into the future. During this phase, the BLM and its partners monitor and maintain restoration measures to support safer public lands and water for today as well as tomorrow.