You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Petroglyphs Hidden in Plain Sight: Insights into the Prehistoric Rock Imagery of Utah’s West Desert

By: Stephanie Graham, Salt Lake Field Office Assistant Field Manager, and Michael Terlep, Salt Lake Field Office Archaeologist

On a chilly yet sunny day in late January, BLM Salt Lake Field Office staff and archaeologists from the Utah State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) ventured across desolate mudflats and windblown tumbleweeds in Utah’s West Desert. The goal of this expedition was to locate and document long forgotten petroglyph sites. Petroglyphs, a form of “rock imagery” or more commonly known as “rock art,” in this area of the West Desert were produced by pecking designs in the soft and patinated limestone and orthoquartzite rocks. The rock imagery was produced by hunter-gatherer cultures of the mid-to-late Archaic periods (approximately 5000 BCE–500 BCE), semi-mobile Fremont agriculturalists (500 BCE–1200 CE), and the protohistoric Ute and Shoshone tribes (1200CE-1850CE). Individuals who created the rock imagery laid witness to dramatic environmental shifts as Lake Bonneville receded into the modern-day Great Salt Lake while vegetation and wildlife ebbed and flowed from lush and abundant to nearly vacant.

Have you ever wandered around the West Desert, stumbled upon rock art, and wondered what the images represent? Utah’s West Desert contains numerous rock imagery spanning the human occupation of the region. Culturally, rock imagery provides an important role for indigenous societies. Similar to television advertisements or roadway signs today, imagery was placed on the rocks to convey a message or amplify a location. Deciphering the exact meaning of rock imagery is often beyond the scope of modern interpretation. When we view rock imagery today, we place our own Western biases into our interpretation. We view these images with all the highlights and cultural perspectives of modern Western society; we access the locations with modern technology and clothing, we carry our own modern perceptions of religion and science, and we assert our own perspective of family and social dynamics. It is also important to recognize that interpreting rock imagery should the left to the modern-day descendants of the people who created it – the affiliated Native American tribes in Utah.

Prehistoric groups who survived on what they could hunt, gather, grow, and make, had a very different worldview from most modern Americans. However, some Native Americans retain cultural connections and stories with their ancestors that produced the rock imagery. Through listening to and learning from them we can better understand this important history.

Archaeologists, including those from the BLM and SHPO, have spent years studying rock imagery and prehistoric/historic societies. They explain that rock imagery often told mythical or narrative stories, provided indications of particular people, property, or territory, and indexed places of cultural or religious importance―similar to a Christian cross or Bodhi Tree today. Research also suggests that some rock imagery mapped the landscape, was associated with rituals or ceremonies before a hunt, or were associated with other rituals or events, such as coming of age ceremonies.

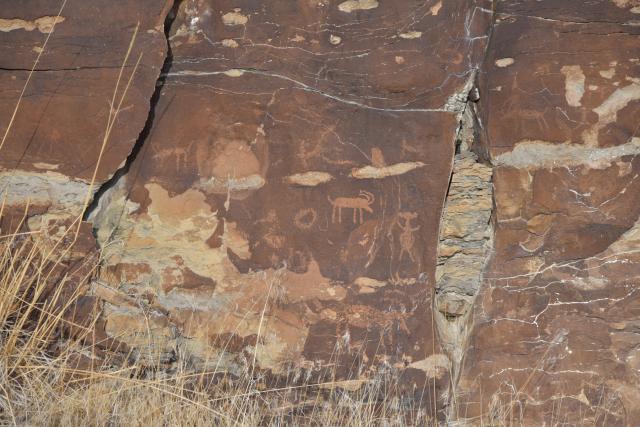

Most rock imagery that you will find in the West Desert is classified as the “Great Basin Abstract” style. This style consists of two primary forms: curvilinear designs with rounded and curved angles, wavy and meandering lines, dots, and circles; and rectilinear designs with right angles, squares, rakes, and triangles. Representational imagery, which includes anthropomorphic (human-like) and zoomorphic (animal-like) designs, were less common in the West Desert during the mid-to-late Archaic period. These designs were often influenced by connections to American Southwest prehistoric populations. Archaic representational imagery features stick figure anthropomorphs and various ungulates, such as bighorn sheep, deer, and elk. As the hunting and gathering lifestyle gave way to semi-sedentary agriculture rock imagery transitioned from more abstract images to more representations of zoomorphic and anthropomorphic forms. Fremont representation style depicts broad-shouldered, static figures often with horn “headdresses” and tapering bodies. Fremont groups in the West Desert appear to continue the legacy of Great Basin Abstract and rock imagery panels often feature both styles.

So why is it important to document these archaeological sites? Recording rock imagery panels is a critical component to their preservation. In 1966 Congress recognized the need to document and protect historic properties as a “living part of community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people.” They also recognized that archaeological and historical sites, places, and objects are irreplaceable to our national history and provide knowledge of our shared cultural heritage. As part of this recognition, Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) which established, in part, federal, tribal, local, and state partnerships to address historic preservation. Section 106 and 110 of the NHPA, as amended, directs the BLM and other federal agencies to evaluate impacts of federally sponsored, funded, or permitted undertakings on historic properties and evaluate such properties for their eligibility to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Through this process, the BLM works with the SHPO to ensure undertakings will not impact historic properties that are eligible for the National Register. Documenting petroglyphs and other artifacts is a critical piece to preserving these items when the landscape and anthropogenic impacts are ever changing. Since rock imagery is located on various land jurisdictions in Utah, collaboration between federal and state agencies is crucial to the documentation, management, and preservation of these significant sites for the benefit of future generations. This project is just one example of a collaboration between the BLM and SHPO, showing how agencies can come together to work towards a common goal of preserving the past.

Next time you are out exploring BLM lands, be sure to keep an eye out for these important sites and remember to leave only footprints and take only pictures. Touching rock art can leave oils and other residue that can be detrimental to its structure, so please be a good steward by keeping your hands and other items off the rock imagery. You can also help the BLM and SHPO by reporting any vandalism of rock imagery to your local office. And remember, rock imagery reveals stories of the past, so let’s preserve it for the future.

If you are interested in becoming more involved with preserving Utah’s past, then consider becoming a Site Steward with the Utah Cultural Site Stewardship Program (UCSSP). As a site steward, you can monitor important rock imagery sites on different public lands in Utah, including BLM land, to ensure they are being preserved for the future. Learn more about the Utah Cultural Site Stewardship Program on the SHPO's website.

Rachel Wooton, Public Affairs Specialist

Related Stories

- Let’s talk about Mustang Camp

- Preserving the past across the Plains: BLM Montana-Dakotas Cultural Resources staff safeguard America’s storied history

- Wild horse and burro adoptions and sales climbed in Fiscal Year 2025, reducing long-term care costs

- Applying for BLM Special Recreation Permits just got easier

- BLM unveils redesigned NEPA Register for easier public access

Office

491 North John Glenn Road

Salt Lake City, UT 84116

United States