You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Bygone buckaroos: Herdsmen offer look at the Hispanic history of Oregon

“Hey there, buckaroo!”

The word buckaroo is a familiar one. To many, it brings to mind visions of cowboys, ranches, open ranges, and cattle drives—the quintessential American West.

Western movies have done much to reinforce this image.

Odds are that conjured image of a buckaroo has them wearing chaps, a Stetson, and perhaps even using a lariat to bring a straying leppy back into a cattle drive.

While widely recognized, few know the buckaroo’s backstory—and its connection to the Hispanic heritage of both Oregon and our nation, highlighted this year during Hispanic Heritage Month.

To understand the buckaroo, you first need to understand the vaquero, the Hispanic herdsman of Spanish and Mexican California from which the word buckaroo originates.

Derived from vaca—the Spanish word for cow—and pronounced vah-kair-oh, the word's Spanish "v" sounds phonetically like the English "b," resulting in the Anglicized word buckaroo.

Try it: vaquero, backero, buckaroo.

In fact, much of the language of cowboys and ranchers, including chaps (from chaparajos, the Spanish name for leather leg armor), lariat (from the Spanish lazo, or long rawhide rope), ranch (from the Spanish rancho), and leppy (a motherless calf, from the Spanish la pepita) comes from the vaquero culture.

In colonial California, vaqueros developed as exceptionally skilled horsemen, ropers, and cattle herders—some of the earliest rangeland experts.

Later, American ranchers expanded north from California to places like southeast Oregon, where they found vast expanses of rangeland unoccupied due to the ongoing dispossession of the region’s Native American population.

These ranchers wanted the best of the best to guide, guard, and grow their herds in Oregon, and they got them.

They hired vaqueros.

In 1869, Juan Redón and around a dozen vaqueros accompanied John Devine’s herd of cattle to southeast Oregon where they helped establish the Whitehorse Ranch southeast of Steens Mountain. It continues as an active ranch today.

Three years later, Peter French and a dozen more vaqueros brought 1,200 head of cattle to the upper Blitzen Valley and, under the auspices of what became the French-Glen Livestock Company, founded the famous P Ranch. (If that company name rings a bell, it’s because it’s the namesake of the community of Frenchglen, Oregon.)

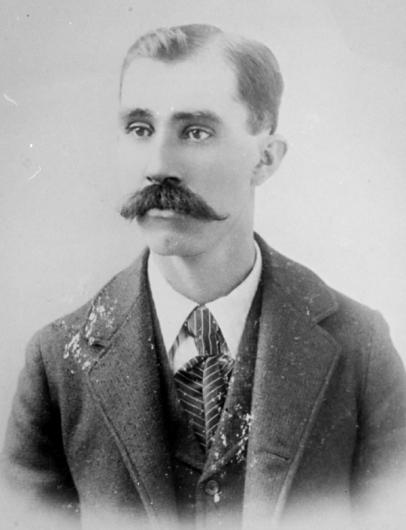

These vaqueros were some of the earliest pioneer residents in southeast Oregon. For more than 25 years, vaqueros like Redón, Vicente and Juan Ortego, Francisco “Chico” Chararateguey, Juan and Jesus Charris, Amado Miranda, Rafael “Chappo” Bermudis, Prim “Tebo” Ortego and Joaquin “Chino” Berdugo rode the range and tended thousands of cattle throughout the Harney Basin.

Herding cattle and breaking horses demanded physical strength, mental acuity, patience, and perseverance. The vaqueros thrived in this atmosphere and ultimately supplied beef that fed citizens, soldiers, and railroad crews in Oregon and beyond.

While some vaqueros returned to California, several remained as settlers.

Records from the General Land Office, administered online by the Bureau of Land Management, show that vaqueros purchased land in the area. Examples include Chino Berdugo in Happy Valley and Catlow Valley, Juan Ortego near Frenchglen and Happy Valley, Tebo Ortego near Frenchglen, and Juan Redón near Whitehorse Ranch.

While many of these claims were later sold by the vaqueros to their employers, they stand as some of the earliest in the region.

Some resident vaqueros, like Tebo Ortego and Chino Berdugo, became pillars of their communities.

Although six feet tall and skinny as a rail, Ortego was recognized as one of the strongest men in Harney County. Oldtimers recalled how he could hold two horseshoes in one hand and no one—no one—could separate them and break his grip.

He was also a trickster and storyteller, known to one-up any wild yarn spun in his presence, to the delight of those around him.

“I worked with Tebo lots of different times,” recalled friend and fellow buckaroo Jinks Harris. “He was a real good buckaroo, too. He was easy and quiet. And he was honest as any man who worked there. As far as the wild tales go, they were just wild tales. When honesty was involved, with borrowing money or anything like that, you couldn’t find a more honest man than Tebo.”

Ortego wasn’t alone.

Known as an exceptional roper, Berdugo aided Catlow Valley homesteaders with everything from ranching to Fourth of July party planning. In return, they named the community of Berdugo in his honor.

“Vaqueros like Berdugo had a lasting influence on the ranching culture of the entire interstate region,” writes historian Jeff LaLande, “introducing characteristic methods of working cattle as well as distinctive outfits—including saddles, ropes, and clothing—to the southwest corner of Idaho, southeastern Oregon, and northernmost Nevada.”

Although most of the vaqueros departed by the 1920s, their influence remained. It permeated and helped define cowboy and ranching culture—and eventually Western film and literature.

Vaquero anglicized to buckaroo, as did chaparajos to chaps, alongside other vaquero lingo.

The word buckaroo soon expanded in definition to describe any cowboy or cattle herder in the American West, regardless of ethnicity.

The word also became a verb that described their work, and “buckarooing” at a ranch is a term still used.

And the buckaroo’s Stetson?

Well, John B. Stetson’s iconic “Boss of the Plains” hat, seen in innumerable photographs and films, is patterned after the broad-brimmed and low-crowned Mexican poblano worn by countless vaqueros.

The vaquero legacy remains connected to the land, too.

Today, places like the Pete French Round Barn State Heritage Site near Diamond and the Frenchglen Hotel State Heritage Site in Frenchglen connect visitors to tangible parts of early ranching life in the region, and resources like the Harney County Historical Society and the Harney County Library’s Claire McGill Luce Western History Room curate stories, photographs, and documents of the era.

And those buckaroos? They aren’t a thing of the past, either.

You can still find them riding the range and buckarooing today.

Greg Shine, Interpretive Program Specialist

Related Stories

- Timber Talk: OR/WA logs a big win in FY25

- Historic Umtanum Suspension Bridge wins international footbridge award

- BLM announces 2025 Rangeland Stewardship and Innovations Award winners

- A beacon through time: The history of Yaquina Head, Oregon's tallest lighthouse

- Proactive work paying off: How forest management made a difference on the Lick Gulch Fire

Office

28910 Hwy 20 West

Hines, OR 97738

United States