You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

Behind the Masks

How Arctic and Fairbanks District BLMers are meeting Alaskan's needs during this pandemic, both on and off the job

Arctic District Office Manager Shelly Jones finished the day with a quick run from home quarantine to drop off cotton face masks at her Fairbanks, Alaska, office for fellow BLMers. She said they look a lot better than the first mask she pushed through the sewing machine that, until late March, beckoned to her unanswered for years. But that was 50 masks ago, or more than 500 depending on how you count them. More about that in a moment.

Six months ago, much of the world may not have known what “PPE” means. But the coronavirus made the term “personal protective equipment” as common as the fact that there aren’t enough masks in the world, despite the CDC’s recommendation that everyone wear one. Jones and other BLMers in Fairbanks are part of an Alaska-wide team shoring up shortages in the state by making and delivering high-quality cotton masks to hospital workers, food bank employees, drivers, and more.

Manager Shelly Jones’

daughter Izzy sports the

first high-quality cotton

mask Jones has ever sewn.

“I’m not a real good sewer, but my sisters and mom are,” said Jones, a lifelong Alaskan who was born in Bethel. “I haven’t sewn in years, but this need inspired me to start again. I got my bobbin wound and found a straightforward pattern I thought I could follow. We didn’t have masks at home, so I started there.”

After about 30 minutes, Jones’ daughter had a mask. 50 masks later, she’s got production time down to about 15 minutes. She’s also delivered about 500 in the past two weeks alone to organizations helping others through this difficult time as part of a group called the Fairbanks Mask Makers.

“It’s like a mutual admiration society,” said Jones. “Those making, picking up, delivering, and receiving masks – we’re all just so grateful for each other. The folks who put this group together are real heroes, and people feel really good that the skill of sewing is being recognized.”

Observing social distancing requirements and wearing PPE herself, Jones spends about four hours on Saturdays for pickups and deliveries. Masks are collected from independent sewers in the area and dropped off to another volunteer who sanitizes them. Jones then delivers batches of sanitized masks to fill orders collected by the Fairbanks Mask Makers coordinator.

Most deliveries go to those in Fairbanks-area organizations helping others through this time of need. Still, Jones was thrilled to also get big shipments of masks out to Fort Yukon before safety concerns stopped flights into the area. Ironically, her contact for the shipment was the same person she had a government-to-government meeting scheduled with a few days later in a Native village.

In an official capacity, Jones and her staff also spend their days making a critical difference for villages in some of the most remote areas of the nation. Although based in Fairbanks, most of the Arctic District spans about 23.1 million acres of Alaska’s North Slope between the Brooks Mountain Range and the Arctic Ocean. Her staff recently championed waiving more than $8,000 in right-of-way fees to get emergency freight to the country’s northernmost city of Utqiagvik. They are also helping pioneer virtual public meetings for land-use plans that reach more Alaskans than ever.

of her handiwork.

Jones has now recruited teammates Arctic District Wildlife Biologist Debbie Nigro and Fairbanks District Office Associate Director Stacie McIntosh to join her in helping the organization fulfill its “huge list of unfilled orders” of masks. In fact, Jones says she leans heavily on Nigro’s skill with “bias tape,” industry speak for strips of fabric specially cut to flex smoothly when sewn around the mask’s curved edges or used to tie the mask to the head. Nigro will also soon join Jones on delivery runs. McIntosh has even begun customizing the masks she builds, using embedded pipe cleaners to ensure a more customizable and comfortable fit.

“Anyone who sews has a stash of material around the house, and those who aren’t sewing have been great at contributing material for masks,” said Jones, “Some need filters and some need ties, but elastic to hold the masks on is in short supply everywhere. People get creative with ideas like repurposing bungy cords and waistbands from clothing that ‘didn’t work out.’ Stacie (McIntosh) has even used Chinese jump ropes for elastic.”

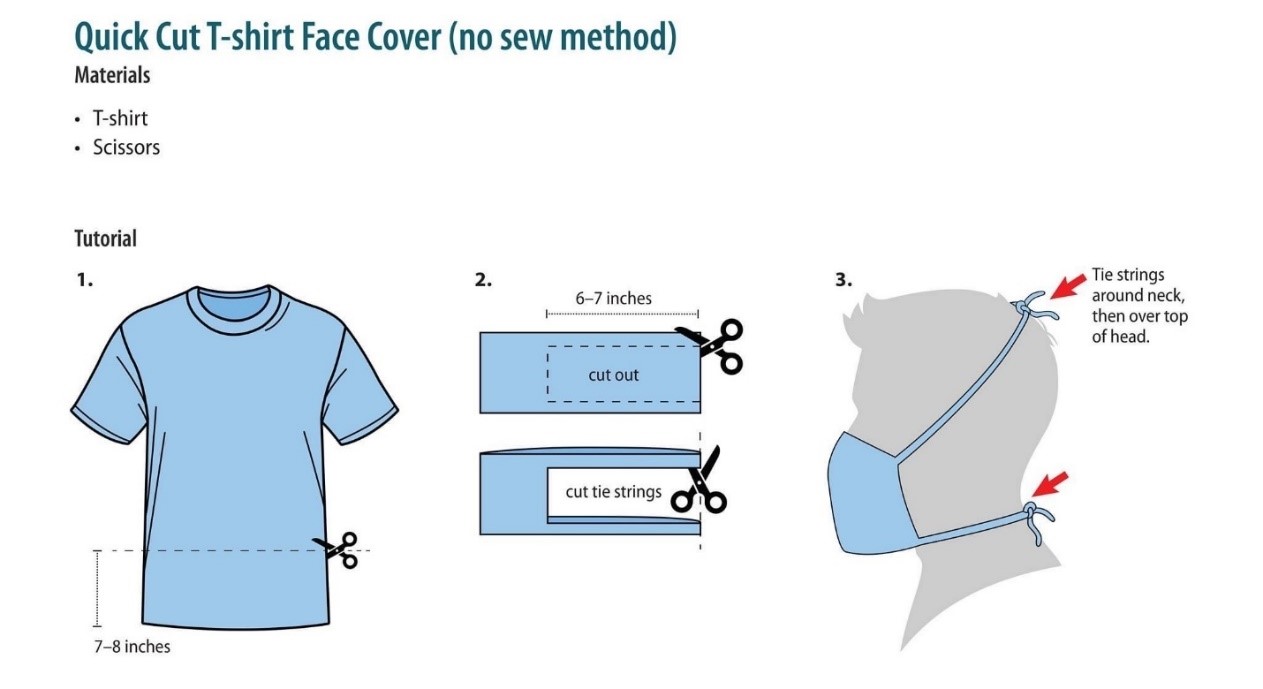

For those without elastic – or sewing skills – Jones and team also have recommendations for making high-quality cotton masks at home using as little as a bandanna or t-shirt (instructions attached to this story). She said repurposing bras, although funny, is also a relatively simple and effective home remedy.

“Helping others like this has kept me connected to both my community and my family,” Jones remarked. “My mom and sisters have probably each sewn hundreds of masks by now. My mom keeps us posted on the best patterns, so this is the next one I am going to try. She says it has the best of all worlds.”

Jones recommends that other interested volunteers in the state contact Alaska Mask Makers or Fairbanks Mask Makers on Facebook.

Eric Tausch, Public Affairs Specialist