Harquahala Peak Observatory | Arizona

Harquahala Peak Observatory was built in 1920 by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory to measure and record solar activity. Although deserted now, from 1920-1925 a hardy group of scientists lived and worked atop the highest mountain in southwestern Arizona (5,681-foot elevation). How these individuals lived, worked, and relaxed up on this peak, struggling with its seclusion and weather, represents an enlivened story of dedicated scientific pursuit and American inventiveness.

Visit the Observatory | History of the Observatory

Visit the Observatory

The observatory is at the top of Harquahala Peak. You can get to the peak via the rugged, 10.5-mile Harquahala Mountain Back Country Byway. A steep hiking trail also leads 5.6 miles to the summit via Harquahala Pack Trail Basecamp Trailhead.

Know Before You Go

- Watch for rattlesnakes and other venomous creatures in the desert.

- Please do not harass reptiles. Many people are bitten while playing with, collecting, or attempting to kill them.

- Remnants of prospecting and mining lie near the Observatory and elsewhere in the Harquahala Mountains. Be aware of the danger these remains pose and avoid them when exploring the area.

- Thunderstorms on Harquahala Peak are often violent and dangerous. Should stormy weather arise during your visit, leave the mountaintop as quickly as possible.

History of the Harquahala Peak Observatory

The Search for the "Solar Constant"

The story of the Harquahala Observatory begins several years prior to 1920 with the vision of Samuel Pierpont Langley. He believed that the sun caused changes in the climate of the Earth and that observation and scientific measurement of the amount of energy reaching the earth from the sun (dubbed the "solar constant") would aid in weather forecasting. In 1887, Langley led an expedition to California's Mount Whitney in the Sierra Nevada to first measure the solar constant.

Langley's protege, Charles G. Abbot, a pioneer in solar research, looked for additional observatory locations with clear skies and low humidity, to continue studies of the solar constant.

In 1920 Abbot traveled to Wenden, Arizona to investigate Harquahala as a potential site. He described his initial impressions of Harquahala in June of 1920 in a letter to the Secretary of the Smithsonian:

The mountain is a good way from Wenden, but can be reached by auto in about an hour or less. The trail is an excellent one five miles long. There is a fine spring halfway up. We walked up in three hours. The lop is quite flat with many rocks, but much green stuff growing, though no trees. I'm very favorably impressed by it as an observatory site.

It has run to 105 (degrees) in the shade every day here, but does not seem more than ordinarily hot. One drinks gallons of water. I could have observed every day so far, although they say it is fixing to rain. The sky is perfectly blue right up to the sun. Mountains stand out as if cut in brass. I believe this will prove a great place for the work.

An Observatory without Telescopes

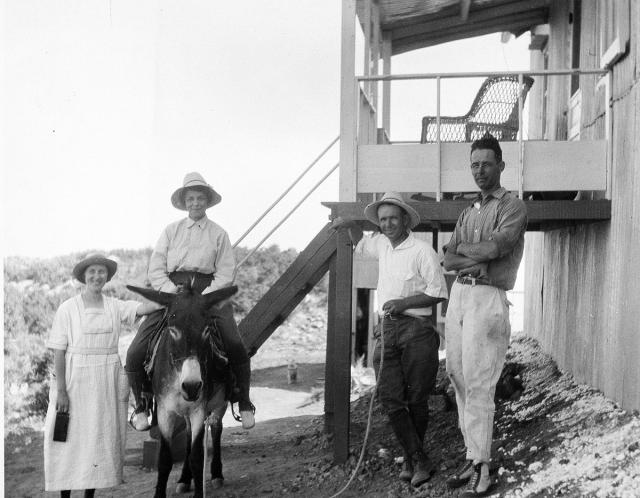

Headquarters for Dr. Abbot's project was established in the tiny hamlet of Wenden and a base camp was located in a canyon 12 miles east, where a couple of small buildings and a corral were constructed. From there a grueling, 5.4-mile-long pack trail on a grade of almost 1,000 feet to the mile was used in order to reach the summit. Pack animals were used to haul lumber, sheet metal, cement, living supplies, and equipment to the mountaintop. Most difficult of all to transport were the delicate recording machines and laboratory equipment. Even water had to be carried by the pack animals until collection tanks could be built.

Dr. Abbot contracted construction for the building and then remained as the first operator. His assistant, Frederick A. Greeley, a cousin, joined him that fall. His yearly salary was $1,600.

Harquahala was an observatory without telescopes. Rather, a theodolite was used for measuring the sun's altitude above the horizon. Two pyrheliometers, mercury thermometers with shutters that opened or closed at set intervals to record heating and cooling, measured energy from both the sun's direct rays and scattered rays. The pyranometer, an electric instrument, measured heat from the atmosphere around the sun. Readings from these instruments supported primary data from a recording spectrometer-bolometer, an electrical thermometer that Abbot claimed to be sensitive to a millionth of a degree.

After the tedious observation and data collection were completed, the raw information had to be mathematically calculated by hand. Reports were sent to Washington for comparison with information taken from another observatory in Chile.

In 1923 solar measurements were first used to predict the weather. The information from both observatories was telegraphed to Washington, D.C. and arrived within twenty-four hours of actual measurement. It was then telegraphed to a weather forecaster in Massachusetts. He made weather forecasts for New York City and returned the information to the Smithsonian the same day.

Life at the Top

Favorable atmospheric conditions made for long work days, but the initial lack of necessities and the daily chores of living made them even longer:

We have observed nearly every day thus far in October. The sky keeps good all day and all night most of the time. Naturally there is a lot to do besides the observing. I get up at sunrise and keep busy till bedtime and still the work looms up before me. Our wood pile at least is getting on and it's very necessary. I have grown into quite a cook. Make lots of nice things to eat. It takes from two to four hours a week to heliograph to Wenden to order stuff and send messages occasionally to Smithsonian.

The heliograph signaled by means of a movable mirror which flashed beams of light to a distance.

The nearest neighbor was Mr. Ellison, a reclusive miner living and prospecting about a mile from the observatory. He lived in a cabin next to a spring-fed creek and cultivated a large garden. He and his pack animals hauled supplies and water but also furnished fresh produce and companionship. Abbot paid him for his services, and as additional compensation, Mr. Ellison enjoyed listening to the Victrola record player on his visits to the observatory.

Gone to Pot

While Dr. Abbot was absent from the observatory in December 1920, difficulties arose:

Found Greeley at station. He had walked 16 miles to meet me. Fine weather continuously during my absence. Everything else gone to pot. Wet and dry thermometers smashed early. Theodolite smashed last Wednesday by a cyclonic gust of wind. Mr. Ellison and burros gone for the winter. Water tank leaks so must lug water a mile hereafter and perhaps supplies five miles. Building showing a fault in wall. Devil appears to have claimed everything. Have to exorcise him.

Abbot and Greeley had to physically haul water, supplies and the 160 pounds of steel needed to repair the structure, to the top of the mountain. The wall sagging was bad enough that Abbot had moved his bed fearing the wall would collapse at any time. He wrote: "It had sagged out about two inches so that a bird flew into my room through the crack. I suppose it was too high to build of adobe. But now it is O.K."

Dr. Abbot left Harquahala in January of 1921 after he was called back to Washington. His post at Harquahala was taken over by his assistant, Dr. Alfred F. Moore, who remained there with his wife, Chella until 1925. Frederick Greeley remained as Moore's assistant until 1923.

Amenities

Alfred Moore initiated many improvements to the observatory such as adding corrugated metal siding to the building's exterior to protect it from the wind and snow and building a porch. He also put in a croquet court. Eventually, Moore and Greeley obtained a Kelvinator and built a refrigerator for it. A Kelvinator was a step up from an icebox, but not quite a modem refrigerator. It certainly had its advantages: "The Kelvinator works superbly and have had ice cream twice already. It freezes just enough ice at one time to supply its demand."

Communicating at Harquahala Peak Observatory evolved from Morse code messages transmitted from a heliograph, to a wireless telephone, to a wire telephone in a matter of three years.

By 1922, telephone line was strung on poles along the pack trail that led down the mountain to Ellison's place. It enabled the Moores and Greeley to communicate easily with Ellison.

Abandonment

Although Fredrick Greeley only stayed on until May of 1923, Alfred and Chella Moore remained until the final days in 1925 when the facility was closed. Citing extreme weather conditions, decreased visibility, and difficult access, the Smithsonian abandoned Harquahala Peak in favor of Table Mountain, California. All furnishings and equipment were removed at that time, and the building stands empty.

Harquahala Peak Today

Harquahala Peak lies on the border of the Harquahala Mountains Wilderness, as designated in the Arizona Desert Wilderness Act of 1990. Motorized vehicles are allowed on the Back Country Byway leading up to the Observatory, but not into the wilderness beyond. No mechanized vehicles are allowed in wilderness areas (including mountain bikes and hang gliders). All motorized vehicles must remain on established roads and trails on public land outside the wilderness.

Contact Us

Activities

Addresses

Geographic Coordinates

Directions

Take Interstate 10 to Salome Road exit. Go north to Eagle Eye Road 9.6 miles then turn right. Go 8.5 miles to the dirt road heading north. Follow the dirt road to the western end of the Harquahala Mountains Wilderness. The byway leading to the observatory is 10.5 miles long and is very rugged and steep in places. Four-wheel drive is required.